Contents:

Alice – A Fight For Life: 25 Years On, by John Willis

Alice: A Fight for Life – The Legacy, by Geoffrey Tweedale

Remembering June Hancock, by Laurie Kazan-Allen

The June Hancock Mesothelioma Research Fund, by Kimberley Stubbs

––Editorial ––

Two noteworthy anniversaries occur in July 2007 that are poignant reminders of the true price paid by ordinary men and women for the commercial exploitation of asbestos.

|

|

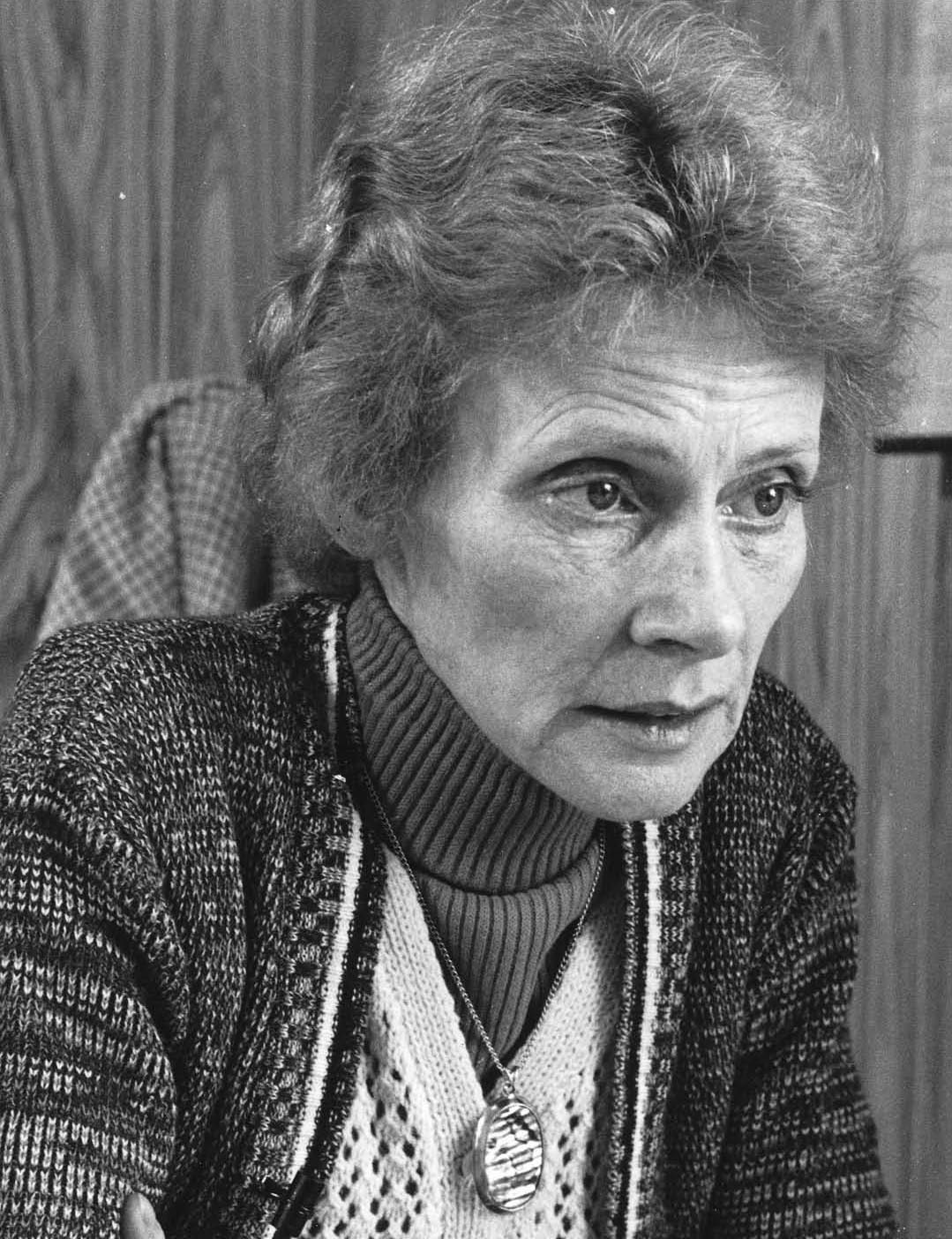

Alice Jefferson |

June Hancock |

July 20, 2007, marks 25 years since the UK's epidemic of asbestos-related diseases exploded into the public consciousness with the broadcast of Alice – A Fight for Life at prime viewing time on national television. The 90 minute documentary graphically illustrated the deadly repercussions of Alice Jefferson's short-term employment at the Cape asbestos factory in Acre Mill, Yorkshire. Watching this wraith-like 47 year-old woman tell her story, it was obvious that she was drawing on finite emotional and physical resources in order to bear witness to what had been done to her and her family. Weeks after the final images of the documentary had been filmed, Alice Jefferson died of mesothelioma, leaving her husband Tom and her children Paul (15) and Patsy (5) to forever mourn her loss.

Although, June Hancock's home in West Yorkshire was more than 50 kilometres away from Acre Mill, it was within spitting distance of another asbestos factory, a happenstance that on July 19, 1997 was to prove fatal. Many residents and workers from Armley, Leeds, including June's Mother, had succumbed to diseases caused by exposure to asbestos spewed into the environment by the operations of Turner & Newall's asbestos textile mill in Canal Road. When June became ill, she knew full well what the future held. In circumstances which would have humbled most people, she emerged fighting, resolved to take on the huge asbestos multinational that had ruined so many lives and broken so many families. That she succeeded in defeating the UK's “asbestos giant” in the High Court and Court of Appeal was due to her thirst for justice, sheer doggedness and ability to inspire others to go that final mile.

This special issue of the British Asbestos Newsletter is dedicated to the memory of Alice Jefferson and June Hancock, courageous women who were murdered by the corporate greed of asbestos producers. Honoring these tragic anniversaries, we pay tribute to their spirit and achievements and pledge our determination to continue their fight.

Alice – A Fight For Life: 25 Years On

by John Willis, Producer/Director: Alice – A Fight For Life

It is both curious and inspiring that 25 years after the transmission of Alice – A Fight For Life it is still remembered and talked about by those who are engaged with such an important part of our industrial history. That is largely because the effects of asbestos can still be felt today.

At the time the impact was immediate and powerful. For a start it drew an enormous mainstream ITV audience. It was shown before the News at Ten and then after it too. Unfortunately, part 2 was delayed until 11p.m. because of the bombing by the IRA of soldiers and horses on Horseguards' Parade. Despite the horror of that story and the long delay 5.8 million viewers watched part 2 of the documentary even though it did not finish until just after midnight. All in all the strong audience figures put Alice into that week's television Top Twenty – an inconceivable impact today.

Such a large audience immediately put pressure on legislators, politicians, and the asbestos industry. Overnight Turner and Newall, the Rochdale-based asbestos giant, lost £60 million on its share price. Within ten days the government had reduced the legal limit for asbestos dust in the workplace still further. At a grass roots level there were demonstrations and marches in several communities. In Sheffield, trade unionists organized a '”Remember Alice” march. But, on a personal note, my greatest satisfaction was seeing Jessie Wellings, a widow from Rochdale, get due compensation because the film proved that her husband's death certificate was wrong and should have mentioned asbestos. Jessie was a great character and deserved every penny (and more).

The impact was so great that the asbestos industry panicked. Private detectives were hired to dig into the character and background of the production team as they tried to smear the reputation of the program producers. But they failed: simply because the power of the film and its underlying truth was such that it overcame any political or commercial spin. As one Swedish trade unionist put it to Alan Dalton, the doughty asbestos campaigner, “you now have the best asbestos regulations in the world thanks to Alice – A Fight For Life.” That is an achievement to be proud of even 25 years on.

Alice: A Fight for Life – The Legacy

by Geoffrey Tweedale

In 1982, over 500 people died in Britain from the asbestos cancer mesothelioma. Few of those unfortunate individuals are remembered today by the public. But time has not effaced all of them, because in that year one person became the public face of asbestos suffering in Britain. Her name was Alice Jefferson and she featured in a TV documentary that carried her name.

Little in Alice's background suggested that she would touch the nation's conscience. She was an ordinary working class mother, who in the early 1950s had spent a few months as a teenager in the Hebden Bridge factory of the Cape Asbestos Company. Working conditions in the asbestos weaving shops were very dusty, but there were no warnings about asbestos and no sign of apparent danger. It was an experience shared by thousands of workers across the country in asbestos factories and shipyards. But in the late 1970s, though only in her forties, Alice began to suffer breathlessness – the first sign that the asbestos fibers she had inhaled in Hebden Bridge had ruined her lungs. By 1980, she was incapacitated with the disease that would eventually kill her – pleural mesothelioma.

At that time, asbestos as a health hazard was still not that widely known to the public and mesothelioma registered even less. The government and many leading physicians had told everyone that asbestos was a vital industry and that manufacture of the mineral was safe. A major government report: the Simpson Committee (1979) had said no less. To be sure, there had been attacks on the industry both before and during this inquiry; there were nine major TV documentaries on asbestos between 1974 and 1982 alone. But in the aftermath of Simpson, the asbestos industry had comforted itself with the belief that asbestos use would continue untrammelled and that the critics had played themselves out. However, around the time that Alice became ill, a Yorkshire TV team, led by producer John Willis and researchers James Cutler and Peter Moore, set out to challenge those comfortable illusions. As the research progressed, Alice became the figure around which their documentary coalesced.

Alice – A Fight for Life was screened on July 20, 1982. As a documentary, it had some unusual features. Not only did it hit a mainstream evening audience, but it was 90 minutes long, and was probably the first documentary to focus so closely on an occupational disease. Never had the public been shown so graphically the horror behind that stock coroner's phrase: “death due to industrial disease.”

Alice opened with Willis in frame, announcing that “In any street, in any town, you'll find what's called the magic mineral … asbestos.” He then explained why it was so dangerous by revealing that asbestos could cause a lethal cancer known as mesothelioma. American legal footage of a skeletal mesothelioma sufferer giving her deathbed testimony demonstrated that the documentary would pull no punches. The film soon introduced Alice, who was to emerge as the “star” of the programme. Over the course of the next hour or so, viewers followed Alice's fate – through the misery of what was left of her daily life, on her tortuous short walks, lying sick in bed, sitting morosely in an ambulance, attending court, through to the final scenes in a hospice. The documentary was interspersed with digressions on other aspects of the asbestos industry – Canadian asbestos mining, production in the developing world, working conditions at companies such as Eternit and Turner & Newall – but always the camera returned to Alice.

Other asbestos sufferers made an appearance, too, such as the redoubtable Georgina, the East Londoner stricken with lung cancer. But much of the documentary's impact was due to its unremitting focus on Alice, who demonstrated enormous fortitude in the face of a pitiless disease. Her physician described her as a “typical West Yorkshire lass. She's tough and realistic and you can't kid this lady. This lady knows exactly what the score is.” Alice's reaction was to fight, especially for her husband and young son and daughter. As she explained: “You just can't give in, can you? You owe it to yourself and your family to keep fighting, don't you. And when you get knocked down, get up and stand there again …” Alice had been offered £13,000 by Cape Asbestos as a settlement, but after she willed herself to attend court, dosed with morphine and scarcely able to stand unaided, that offer was increased to £36,000. Alice remarked that it was not much, when what she needed was a new body.

Against this backdrop, Willis's team ripped through the myths surrounding asbestos and emphasized the dangers of environmental exposure and the toxicity of white asbestos (besides the blue and brown varieties). In particular, Alice exposed the compensation scandal that left many victims and their families, not only bereft but in poverty. Its heaviest punches were reserved for the asbestos companies, especially the industry leader Turner & Newall in Rochdale which had declined to take part in the program. Alice highlighted not only the appalling levels of compensation for asbestos diseases, but also the collusion of physicians and the government in covering up the extent of these mortal illnesses, so that even the most miserable pittances were never paid.

The documentary's impact was far reaching. As Wilf Penney, the asbestos industry's PR man, put it: “Until the Alice film the various programmes on asbestos made since 1975 had little lasting impact on either the public or the industry … [but Alice] … was a different kettle of fish. It was a highly personalised, very emotional tragic record of one person's suffering. It was two years in the making and was, to put it mildly, a blockbuster.” It hit Turner & Newall's share price and triggered public outrage around the country. The outcry forced the government to act. It had quietly sidelined the Simpson Committee's recommendations for lower dust levels in the factories, but within days of Alice these were suddenly implemented. The government then had the effrontery to deny that this was the result of pressure from the media and the public.

Another effect of the documentary was that it highlighted many recent injustices – a few of which could be reversed. Many grieving relatives suddenly appreciated that they had not been told the full story. On October 15, 1982, the New Statesman ran a story titled Cover-Up on Asbestos Victims, which showed how coroners had denied inquests to T&N's workers, while the medical men had somehow suffered memory lapses about asbestos-related diseases when filling in death certificates. Alice did not end the compensation scandal, but it made everyone more aware of the true cost of industrial disease and how the state conspired to hide it.

Faced with this onslaught, the asbestos industry counterattacked. Sir Richard Doll – who regarded the documentary as “harmful” – was invited to Rochdale by Turner & Newall to reassure its workers that the risks of asbestos were negligible. The program makers were categorized as “subversives” and the industry made attempts to get the film censored. An official complaint was made to the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA), but the complaint was rejected and attempts to undermine the integrity of the program failed – not least because the renewed scrutiny showed merely that the charges of cover-up were well-founded. Alice was shown in the U.S. and in Europe, where the documentary won prizes. It was recognized as a path breaking work that had put Britain (and other countries) on notice that asbestos was a major hazard. No one would ever look at asbestos in quite the same way again.

And 25 years on? Alice remains one of the most harrowing documentaries ever made and also one of the most effective. Perhaps its most depressing feature is that the problems it highlights have not disappeared. Deaths such as Alice's from mesothelioma, far from becoming rarer, have actually increased (at the present time to nearly 2,000 a year in the UK – four times the figure in 1982! And about 300 of those mesothelioma deaths are women, whose mesothelioma rate has increased five-fold since about 1970). Compensation, in the face of company restructurings and insurers' machinations, remains as fraught and uncertain as ever. Many of the environmental dangers highlighted by Alice, such as exposure from asbestos in buildings, are still with us. Moreover, asbestos manufacture – as Alice highlighted – has moved to the developing world, where another young generation are being exposed to asbestos fibers and may become victims. In 2007, the documentary is as relevant as ever. So, too, is Alice Jefferson's exhortation to fight and never give in.

by Laurie Kazan-Allen

Twelve years after losing her mother Maie to mesothelioma, June Hancock came face to face with the nightmare once more; after months of lingering illness which would not surrender to diagnosis, a doctor in Killingbeck Hospital confirmed June's worst fears: her difficulty in breathing, her lethargy, and the collapsed lung were neither flu nor tuberculosis: she too had contracted mesothelioma. June could not believe that lightening could strike twice; she said:

“The possibility of me getting this was something like a million to one – that there should be two in one family. It never for a moment occurred to me. I'd always followed stories in the papers about Armley and asbestos but I never thought it would touch my family again.”1

June knew how the disease would progress; she knew that everyday tasks would become increasingly arduous and current pleasures unobtainable. June's Yorkshire puddings, served as a first course Northern style, brought the entire family flocking to her dining room table for Sunday dinner: children Kimberley, Russell and Tommy, their partners Michael, Joanne and Janet and grandchildren Kelly and Gareth. Lack of breath would put an end to this happy ritual. Taking her beloved dogs Bruce and Sophie onto the Chevin, cheering Leeds United on – the illness would make both impossible. June had witnessed her Mother's decline and knew what lay ahead for herself and, what was worse, for her family.

With her eyes wide open, June chose to fight back. Her opponent, J. W. Roberts Ltd. (JWR), had been operating from the Armley site since 1895. In 1920, it had become a subsidiary of Turner & Newall (T&N) Limited. The parent company handled “all questions of general policy or finance which affect either the group as a whole or any particular unit company.” The relationship between head office and JWR was particularly close: JWR functioned “in effect as managers or agents for Turner & Newall Limited.” So, by suing JWR, June was in reality suing T&N. In 1995, T&N's 40,000 employees generated a £2 billion turnover at two hundred installations in twenty-four countries; the company wasn't about to give in easily. Undaunted, June instructed a solicitor shortly after she was diagnosed; a writ was issued on September 5, 1994. June wrote:

“Whether we win or lose the case is absolutely unimportant. I would like to win of course. But the money side is absolutely and totally irrelevant. It certainly won't do me any good... The fact we have got them to court is what matters. It's out in the open. They've got to stand there and be answerable for what they've done...I feel sure they'll be guilty some day. But if we do win, it will be easier for others.”

It was a test case; never before had anyone succeeded in getting compensation for environmental asbestos exposure from an English company. Mesothelioma is always fatal; the Court recognized the need to expedite proceedings. June's case was combined with that of Evelyn Margereson, the widow of a mesothelioma victim who had, like June, lived near the Roberts' textile factory. For more than two years, John Pickering, Mrs. Margereson's solicitor, had been battling with the defendants over discovery. In the judgment handed down on October 27, 1995, the Honorable Mr. Justice Holland referred to the defendants' behaviour:

“I presently explain the discovery history as being of a piece with other features of the conduct of the defence – that is, as reflecting a wish to contest these claims by any means possible, legitimate or otherwise, so as to wear them down by attrition. Thus it has not just been with respect to discovery that the Defendants have remorselessly persisted in taking bad points, apparently simply to obstruct the Plaintiffs' road, heedless of the inevitably adverse effect upon the trial judge.”

Holland's sixty-six page ruling focused on the duty of care the factory owners had to their neighbors and others who came within the environs of the industrial unit. In the 1930s and 1940s, children played outdoors; flat, open spaces were particularly attractive. The Aviary Road loading bay was ideal for roller skating, hopscotch and other games. One witness recalled:

“sometimes sacks were left out overnight. They were hessian sacks and they were full of a sort of fluffy dust. We could jump on the sacks when they were left out... I remember seeing grey blue coloured dust come out of them. If we jumped hard enough the sacks burst open. After sitting or bouncing on the sacks I remember being covered in dust.”

It was raw asbestos fiber and waste which came bursting out of these sacks. Holland concluded that a duty of care had been owed to those like Arthur Margereson and June Gelder, as she was then, who had come:

“within the curtilage of the factory...there was knowledge, sufficient to found reasonable foresight on the part of the Defendants, that children were particularly vulnerable to personal injury arising out of inhalation of asbestos dust...reasonably practicable steps were not taken to reduce or prevent inhalation of emitted asbestos dust.”

In his High Court judgment, Justice Holland paid a “warm tribute to her (June's) dignity and courage.” Strange words from a judge but then he was only reacting as others had done: Vanessa Bridge from the Yorkshire Evening Post, Adrian Budgen, her solicitor, Robin Stewart QC, her barrister, Andrew Spink, her junior counsel, M.P. John Battle and her consultant Dr. Martin Muers were all touched by June; all kept faith till the end and beyond.

The relief of the lower court's verdict was short lived; an appeal was lodged. During the last week of March 1996, Lord Justices Russell, Savile and Otton heard submissions in London. The appeal was dismissed on April 2, 1996; permission to appeal to the House of Lords was refused. And so it ended: June Hancock received £65,000, Evelyn Margereson £50,000. Not much for two lives. But what a stunning victory! June and her legal team were jubilant; June's words were quoted nationally: “It proves however small you are you can fight and however big you can lose.” After the verdict, other mesothelioma victims from Armley and Washington, the location of another T&N subsidiary, received out-of-court settlements. June was right; her fight had made it “easier for others.”2

June defied the doctors. In January, 1994 she had been given two years to live. Despite her illness, she attended Leeds High Court every day bar one of the six-week trial. She endured the uncertainty of the appeal and the press attention after the London victory; “stubborn resistance” and her thirst for justice won her an extra eighteen months. In the end though, even she was unable to reverse the biological consequences of a childhood spent amidst clouds of asbestos dust. For three and a half years, the children managed to comply with her wish to keep everything “as normal. as possible,” but by June 1997, the pain had become so bad that hospitalization was the only option.

The family arranged a visiting rota: Michael's shifts enabled him to cover some of the odd times. Difficulty in sleeping meant that June was awake much of the night. One night, Michael took her for a walk. How the two of them were not stopped remains a mystery – June in dressing gown and slippers, attached to an oxygen cylinder behind the wheelchair gliding along the Leeds to Bradford road at 3 o'clock in the morning. On Thursday July 17, 1997 June's condition took a turn for the worse; the family were called. They were there; they were all there. On Saturday afternoon, June sat up. Russell says: “I don't know what she wanted to do... maybe to speak to people. The drugs made her so tired. She wouldn't lay back down and she was very weak by then. I put my arms round her and said: look we're all here. She laid down and that was it. That was the last time she ever moved.” She died that afternoon.

********************************************************************************************

Remembering June, her daughter Kimberley wrote:

“My Mum was full of love and life. She was gentle, funny, selfless and hardworking. All my memories are special and happy, we were like best friends. She was simply beautiful and did not deserve to die so young. I lost my adored Mum and the world lost an angel on the 19th July 1997. Things could never be the same again.”

********************************************************************************************

Frank Gelder, June's father, lived until he was 86. Who can say whether June would have enjoyed the same longevity had it not been for Turner & Newall? Another 25 years of good times, family dinners and happy memories. A time during which June could have enjoyed the grandchildren she had so longed for, children she never got to hold or love: Andrew, Jonathon and Emily June; the joy of watching Kelly & Gareth, June's older grandchildren, grow into the wonderful young people they have become was also denied to her by a corporate murderer.

In a society grown cynical and suspicious, June's bravery shines ever brighter; her struggle for justice is not forgotten and our memories of this lovely Yorkshire “lass” remain undiminished.

The June Hancock Mesothelioma Research Fund

by Kimberley Stubbs

The June Hancock Mesothelioma Research Fund3 was established in 1997 shortly after June's death from mesothelioma by family and friends wishing to carry on June's quest to conquer the evil cancer: mesothelioma. So far donations totalling in excess of £350,000 have been received, mostly in small donations from those personally affected by the disease.

The June Hancock Mesothelioma Research Fund aims to:

encourage and sponsor vital epidemiological research into the causes of mesothelioma, and the exact part that asbestos plays in its causation;

contribute to clinical trials with novel drugs therapies for mesothelioma;

raise awareness of the disease amongst healthcare professionals and the public at large;

provide good quality, easy to understand and up to date information and advice for mesothelioma sufferers and their carers, through published material, a national helpline and periodic conferences and educational seminars;

achieve delivery of the Mesothelioma Charter as soon as possible.

The Fund has supported research projects in Leicester, Glasgow, London and Cardiff and has underwritten 10 multi-professional educational events. Closer to home, a donation to the Ridings Asbestos Support & Awareness Group (RASAG) facilitated the opening of an office in Armley, Leeds where people can obtain much needed advice and support either in person or by phone. The donation to the MSO1 pilot trial enabled the preliminary work on that very important research project to be conducted; the disposition of a further £100,000 to UK mesothelioma researchers is now under consideration. Ten years after June's death, the work which was so dear to her heart continues.

My Mum, June Hancock, came to know many special people throughout her illness and legal battle, from barristers to journalists, from solicitors to medics, from legal secretaries to other individuals suffering from mesothelioma. She would often speak proudly and fondly about the wonderful friendships she had made. Many of these friends were involved in the setting up of The June Hancock Mesothelioma Research Fund in June's honour and spirit. The fact that the Fund goes from strength to strength is testimony to the profound impact that she had on all who knew her and loved her. The dedication and commitment of these wonderful people is overwhelming, and deserving of the highest recognition and appreciation. Like June, I feel privileged to call them my friends; together we continue June's battle for justice.

___________

1 As a child, June had lived in Armley, the location of the J.W. Roberts' asbestos textile factory.

2 When Turner & Newall Ltd. went into administration on October 1, 2001 these payments ceased. Under the recent settlement which allows Turner & Newall to exit the administration process, £33 million has been put into a UK Asbestos Trust Fund to pay compensation for claims including those from UK residents who lived near T&N asbestos factories; there has been no news, however, of any such payments having been received by the date of writing (July 10, 2007).

3 JHMRF website: http://www.leeds.ac.uk/meso

___________

Compiled by Laurie Kazan-Allen

ÓJerome Consultants